The Problem of Christian Passivity

The belief that boldness is for God alone is radically unbiblical. Now more than ever, it is time to cast it aside.

As an anti-Christian teenager, I enjoyed challenging Christians about their faith. The arguments I made against Christianity were not original or very well-researched: I cannot have read more than three books on the subject during my whole adolescence. Yet the dynamic of each conversation seemed to prove that I was winning.

In the world of Christian apologetics, it is not uncommon to encounter atheists who are both well-read and charitable. My own hostility to Christianity was more typical of the vast majority of anti-Christians: my arguments were unoriginal because I was not all that interested in developing them. Like most secular Westerners, this did not stop me from having a strong opinion, nor from believing that I had discovered that opinion myself.

What really fueled my confidence was not that Christians were intellectually unprepared—although it helped that they were. Instead, my hostility was excited because I perceived Christians as showing weakness. I don’t mean that the Christians I confronted explicitly conceded defeat. I mean that the believers I challenged seemed to approach almost any clash of ideas with an attitude of passivity. They avoided staking out bold positions, took great care not to say anything that might be offensive, and generally went beyond mere civility and into demurity.

During one such conversation, I recall thinking that I’d made a discovery: that Christians secretly knew that I was right and that their faith was a lie. Far from being winsome, which is probably what these Christians had intended, the impression that Christians were doormats encouraged me to be even more aggressive in my opposition. The compliant agreeableness of Christians did not soften my hostility. Instead, it put blood in the water.

I also remember the very moment when I first began to consider Christianity in a new and different light. A man had handed me a paper tract earlier in the day and, propelled by some unusual circumstances, I found myself looking through it. The content of the tract—although not quite fire-and-brimstone—was clearly intended to be provocative. As I looked at the tract, it suddenly struck me that Christianity might not be, as I’d thought, something that a person trying to rationalize cowardice would invent. This experience didn’t convince me that Christianity was true—that didn’t happen until much later—but I did catch myself viewing Christianity with a new kind of respect.

In Michel Houellebecq’s near-future novel Submission, the protagonist—a degenerate atheist academic—begins to search for meaning in religion after confronting the deadening emptiness of his secular lifestyle. But, after briefly spending time in a monastery, he contemptuously casts Christianity aside, concluding that it is “a feminine religion,” capable only of surrendering to and being subsumed by Western modernity. Instead, Houellebecq’s character joins an increasing number of Western Europeans who are finding a new source of meaning in an ascendant Islam. When Western Europe finally repents of the yoke of nihilism, Houellebecq seems to imply, it will be the strong horse of Islam that rings true—not the Christianity that politely surrendered to that nihilism in the first place.

In their excellent essay series Christianity’s Manhood Problem, Brett and Kate McKay claim that Christian churches tilt so heavily female that—although Christianity is actually the only world religion with a significant gender disparity—Christians single-handedly skew the average for all religions, giving the false impression that women are more religious than men in all cultures. The McKays persuasively argue that this female slant does not result from anything inherent in Christian theology, and that the feminine attributes of Christianity have been artificially privileged over its masculine ones. “Hypothetically,” they write, “the lion thread of Christianity might have been ascendant, or equally yoked with its lamb side. And for a time, it was.”

I largely agree with what the McKays say about “the feminization of Christianity.” Yet I think that Christian passivity should be recognized as a distinct but related problem. Thus, in this column, I’ll review the nature of the problem and what might be done to counteract it.

The best way to define what I mean by “Christianity passivity” is likely through an illustration. Imagine you are in a setting in which other Christians are present, and a secular person enters and begins to strenuously denounce Christianity. Suppose that, rather than attempting to make any defense of your faith, you allow the person to proceed unopposed, perhaps thinking that simply being polite is the ideal Christian response. If so, you can be sure that the other Christians present will probably think nothing of this reticence. Your fellow believers will almost certainly not regard you as having done anything suspect or un-Christlike.

But now imagine that, rather than remaining passive, you rise to the occasion and firmly engage with the critic’s arguments, even going on the offensive against his own views. In this case, it goes without saying that your behavior is likely to be frowned on by some of the other Christians present, who might conflate any energy in your argument with unkindness. And if you do genuinely cross the line into rudeness, this offense is going to be judged far more severely than had you said nothing at all, and utterly surrendered the floor to the atheist.

1 Peter 3:15 famously commands Christians to always be “prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect.” The word “defense,” or “ἀπολογίαν [‘apologia’],” connotes an accused person’s defense of himself in court, as in the Apologia of Socrates. Yet, in the popular interpretation of this verse, the subordinate clause of the sentence has somehow chewed up and eaten the main clause. It is almost a cliché that, when apologists remind Christians that they are commanded to be “prepared to make an apologia,” someone will chime in to quote the subordinate clause of the sentence as if it cancels out the main clause, or as if to suggest that “gentleness” itself is the “defense.” This is not unlike the way that people are fond of quoting the words “render unto Caesar” while omitting the part of the sentence containing Jesus’ main point.

To take a larger illustration, consider Chick-fil-A’s recent decision not to renew funding for The Salvation Army and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and to instead give to certain secular charities. Despite many Christians’ initial hopefulness that this was a coincidence, Chick-fil-A executives have stated clearly they made this decision to avoid controversy.

“There are lots of articles and newscasts about Chick-fil-A [accusing the company of homophobia], and we thought we needed to be clear about our message,” Chick-fil-A’s president, Tim Tassapoulos, told reporters. The executive director of the Chick-fil-A Foundation, Rodney Bullard, told Business Insider that Chick-fil-A was refocusing on being “relevant and impactful in the community… [f]or us, that's a much higher calling than any political or cultural war that's being waged.”

Of course, while giving to Christian charities is morally valuable, there is no question that giving to secular charities is also praiseworthy. Many Christians have therefore convinced themselves that, because Christians do not have a per se duty to give to Christian charities, Chick-fil-A has not done anything wrong. For example, Franklin Graham—coming to his friend Dan Cathy’s defense —said that “[Chick-fil-A] announced that in 2020 they’re giving to fight hunger and homelessness and support education. What’s wrong with that?”

The premise underlying this argument seems to be that it is acceptable for Christians to calculatedly attract the smallest amount of controversy they can possibly conceive of. To Graham, and Chick-fil-A’s other defenders, whether Chick-fil-A is boldly asserting Christian principles is irrelevant. Instead, the only question we should ask is whether Chick-fil-A is doing something actively and directly contrary to those principles. So long as the answer to that question is “no,” Graham suggests, Christians have nothing to object to.

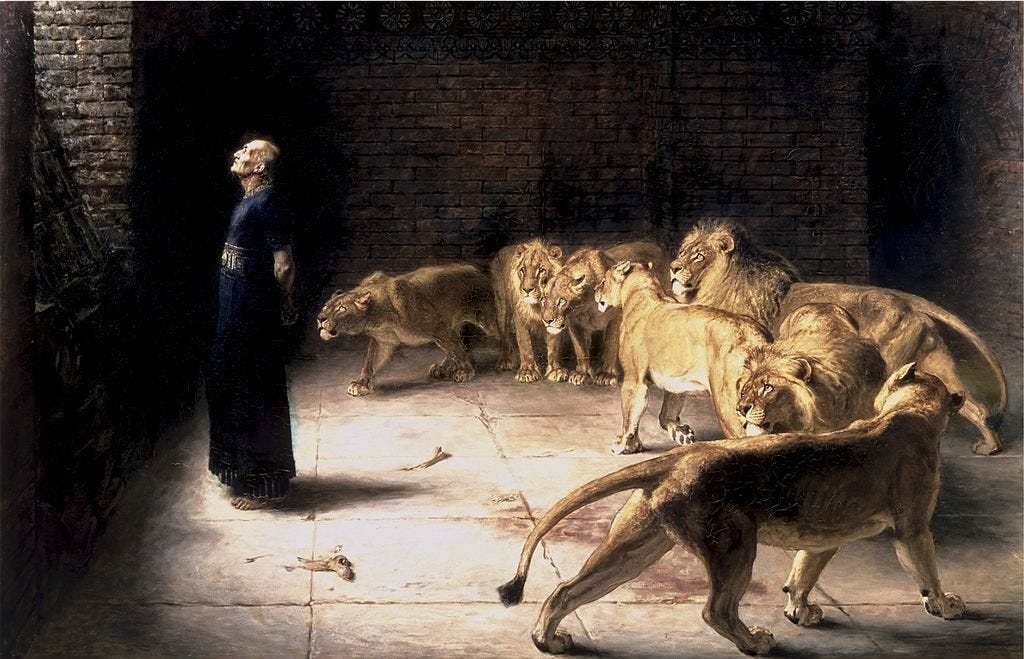

In contrast to this attitude, consider the famous story of Daniel 6. Persian officials had persuaded Darius to pass a law decreeing that “whoever makes petition to any god or man for thirty days, except to you, O king, shall be cast into the den of lions.” In his commentary on Daniel, John Calvin pointed out that Daniel could have responded to this law with timid hairsplitting, such as by waiting to pray until after the thirty days had expired, or praying silently to himself. Instead, Daniel went straight to his house, opened his window, and prayed out loud three times a day, “as he had done previously.” In the words of the church father Theodoret, "when [Daniel] got news of the passing of the law, he had great scorn for it and continued openly doing the opposite… he said his prayers not in secret but openly, with everyone watching, not for vainglory but in scorn for the impiety of the law." Even though Daniel did not have a duty to pray out loud in the first place, he responded boldly as soon as his religious practice was infringed upon. By demonstrating his open “scorn” for the law, Daniel both glorified God and framed the narrative around the law, rather than allowing it to be framed for him by the officials.

Paul makes a similar point in 1 Corinthians 8-10: for Christians, the physical act of eating food sacrificed to an idol is itself lawful, for “an idol is nothing at all.” Yet Christians should not be seen eating the food of idols, lest other people “be emboldened to eat what is sacrificed to idols” by an apparent compromise with idolatry. Christianity therefore takes an approach that is the opposite of certain other religions, which allow the believer to conceal his religious beliefs when they are disfavored. Under a biblical worldview, when compromises related to God are on the table, it is time to go into battle, not to retreat.

If Daniel had adopted the strategy approved by Franklin Graham, he might have just prayed silently, demurely accommodating his worship to socio-legal convenience. “So he’s praying silently—what’s wrong with that?” we can imagine Franklin Graham saying.

Likewise, it is now the norm that, when their standing in society is threatened, Christians passively withdraw from the edges of the Overton window and allow it contract around them. If repeated multiple times, this process will result in Christians squeezing themselves into a smaller and smaller range of allowable discourse, like a mouse being eaten by a boa constrictor.

This is an uncanny reversal of the history of the church—a kind of Benjamin Button version of church history. From its inception, Christianity has involved a fervent rejection of all the Overton windows surrounding it. Christendom persisted and filled the world through the force of an uncompromising zeal. The historian Rufus Fears powerfully described the effect of the Emperor Diocletian’s attempt to systematically exterminate Christianity:

Instead of breaking Christianity, it only seemed to strengthen it. And non-Christians who watched these men and women—these girls, even, and boys who were Christians—stand up to the Roman bureaucracy and say ‘No, I will not worship your gods: put me to death.’ There must be something in this idea that gave it power.

After emerging from the Great Persecution, the church triumphed in the religio-civil wars of Constantine and Theodosius. Yet, far from being co-opted by imperial authorities—as is often represented—the church always maintained a separate sphere of power, from which it could check the influence of the state and culture. From Ambrose, to Thomas Becket, to De Las Casas, the church’s boldness enabled it to bring vast political and economic systems to their knees for much of the last two millennia.

So how did the church founded by Jesus Christ, whose force of personality reverberates throughout the Gospels and shook the core of Western civilization, come to take on the one-dimensional meekness of contemporary Christians? The most obvious answer is that the character of Christ himself has been subjected to layers of editing. I'll focus on two of those layers in particular.

First, Christ’s zeal is consistently erased or minimized. It goes without saying that there are few contemporary Christian songs in which Jesus clears his father’s house with a scourge, menaces people with talk of millstones, or appears with eyes aflame with fire. Nor does the Jesus depicted in most sermons seem to preach frequently about hell, or to scorn the flavorless and lukewarm. He rarely, if ever, talks of coming to bring a sword or of casting fire upon the Earth.

And when someone does bring up these less-than-polite facets of Christ’s character, the defender of Christian passivity is always ready to evade them, asserting that Christians are only supposed to imitate one half of Christ's attributes and ignore the other. We should immediately be suspicious of this standard—which just happens to minimize social inconvenience—since it cannot explain the church’s exclusive focus on the most agreeable aspects of Christ’s personality. Even if Jesus showed us His burning zeal for reasons exclusive of ethics, it must still be true that Jesus showed us that zeal for a reason. Rather than grappling with what that reason might be, passive Christians prefer to ignore it.

A more penetrating question is where the defenders of Christian passivity find any hint in the Bible of the notion that we should not imitate Jesus. Jesus himself certainly never said “do not imitate these things I am doing.” Nor is that how Paul understood Christ’s message: Paul commanded us to “imitate me as I imitate Christ.” Paul, in turn, intentionally started a riot in the Sanhedrin and joked that his opponents in the church should castrate themselves. The worshipers of Milquetoast Jesus, accordingly, do not seem enthusiastic about imitating Paul either.

Some try to justify this division by pointing out that “Jesus is God and we are not,” or similar words to that effect. The problem with this argument is that it applies equally to Christ’s other attributes. If someone tells a haughty Christian leader that he should serve others as Jesus served, it is obviously no excuse for that leader to reply, “Jesus is God and I am not,” even though this statement is factually correct. The rule cannot be that Christians are to “be imitators of God” if the mere fact of Jesus’ divinity is a reason not to imitate him.

A second argument—one less outwardly vapid—urges that “while Christ’s harsh language is always righteous, ours is tainted by sin.” Like the previous argument, the statement is entirely factually correct, but does nothing to justify the implied conclusion.

The problem with this argument it is not that it observes that human anger is sinful, which is obviously true. Instead, the problem is that it assumes that human passivity is not sinful—or, at least, that it is less sinful than anger. But this is simply begging the question: the argument commits the very practice it is trying to defend, assuming a standard of passivity and then reading the Bible according to that standard.

What, then, do biblical ethics teach us about passivity? To begin with, if passivity is good, or even preferable by comparison to anger, we would not expect Jesus to single out sins of inaction as particularly egregious. Yet this is precisely what Jesus does.

In the story of the sheep and the goats, for instance, Jesus does not castigate the goats for sins of commission, but for sins of omission: that is, he condemns them for things they failed to do. The same thing is true of Parable of the Talents, in which Jesus condemns a “wicked and slothful servant” for failing to serve his master proactively. Notably, both stories end with Jesus banishing the offender to hell. Passivity is therefore not some magical safe harbor from the taint of sin. On the contrary, Jesus seems to treat it similarly to material riches: as a stumbling block that is especially prone to separating human beings from God.

The Bible also presents passivity as sinful in direct terms. To take the most well-known example first, consider Peter’s denial of Christ. When Jesus asked Peter “Do you love me?” three times in John 21, this seems to have wounded Peter far more than when Jesus called Peter “Satan” in Mark 8. Yet Christ delivered the rebuke, not because Peter was sometimes abrasive—which he was—but because Peter had been a coward. Peter’s denial of Jesus—a sin committed specifically to avoid conflict and its consequences—is presented as a profound betrayal of Jesus, not a minor offense. This fact, by itself, refutes the idea that conflict-avoidant meekness is somehow the standard of goodness.

Likewise, when God warned Ezekiel about what would happen if Ezekiel did not “speak to warn the wicked from his wicked way,” He was not warning Ezekiel away from being overzealous, but from being too passive. This verse—Ezekiel 3:18—has been cited throughout church history by Christians who have taken bold positions, such as Ambrose of Milan when he barred the Emperor Theodosius from communion in 390, or by Gregory VII when he excommunicated Henry IV in 1076.

The reason the Bible condemns passivity is because it leads to hellish suffering and hell. In some of the most grotesque passages in the Old Testament, the authors condemn cowardice using the motif of a man who will not risk his safety to defend his wife from sexual abuse. This occurs in Judges 19, in Genesis 12, 20, and 26, and in 1 Kings 20. One striking aspect of these stories is that they present pure inversions of the Gospel. Christ loved the church as His bride, and therefore gave Himself up for her sake. In contrast, the man in each of these stories loved his own bride so little that he was willing to give her over to be raped for his own sake. He committed, in other words, an act of pure evil.

Appropriately, then, Revelation 21 lists “the cowardly” first among those who “will be consigned to the fiery lake of burning sulfur,” together with “the unbelieving, the vile, the murderers, the sexually immoral, those who practice magic arts, the idolaters and all liars.” The Greek word translated as “cowardly,” “δειλοῖς,” connotes—among other things—being agreeable in order to avoid conflict. In the Iliad, for example, Achilles tells Agamemnon “Surely I would be called cowardly [δειλός] and of no account, if I am to yield to you in every matter that you say.”

I note with some hesitation that, while the Bible also condemns sinful anger, or “Ὀργίζεσθε,” this word does not appear in Revelation 21’s pantheon of evil. I mention this not to make light of sins of anger—which I know firsthand can be ruinous—but because Christians have committed the opposite error. We assume that sins of passivity are less deadly than sins of zeal but, if anything, the inverse is true. When Simeon and Levi defend their sister by massacring the entire male population of Shechem, there may be a suggestion of moral judgment from the author. But this judgment pales in comparison to the nihilistic abyss of Judges 19. By the end of the story, the Levite protagonist seems like Tolkien’s Gollum: a withered creature barely recognizable as a human being. This is “δειλοῖς [cowardice],” one of the fathers of all sin, in all its wretchedness.

Christian passivity has gone even further, and altered our perception of biblical events. More than once, for instance, I’ve heard some Christian suggest that—when Jesus cleared the Second Temple—he carefully cracked his whip over the heads of the money-changers, doing so without ever striking anyone. Importantly, this is something you would never guess by simply reading the biblical accounts without any preconceptions. In fact, if Jesus had done something so bizarre, you would expect at least one of the Gospel authors—who saw Jesus as a model for human life—to notice and remark on it. Yet none of the four Gospel authors even hints that this is what Jesus did. The interpretation that Jesus did not strike any of the money-changers therefore imports the presumption that Jesus practiced some sort of ahimsa-like avoidance of violence rather than allowing the text to speak for itself. Until recently, I was unaware of any self-identifying Christian leader—outside of Christian pacifism—who actually taught this interpretation. Unfortunately, Pope Francis appears to have done so in an address last year. “[The clearing of the Temple] certainly wasn’t a violent action,” said Francis. “So true is this that it didn’t provoke the intervention of the guardians of public order – of the police. No!” The suggestion appears to be that, because the police did not come into the Temple and arrest Jesus, he must not have struck any of the money-changers.

It would be charitable to characterize this argument as ignorant. We don’t need any special explanation for why Jesus was not arrested in the Temple—because the Gospel authors tell us directly. Later in the same chapter, Matthew tells us that “although they [the Pharisees] were seeking to arrest [Jesus], they feared the crowds, because they held him to be a prophet.” Mark, in the very next verse after the Temple is cleansed, writes that the Pharisees “feared him [Jesus], because all the crowd was astonished at his teaching.” Luke, immediately after narrating the cleansing of the Temple, says that Jesus and his followers then occupied the Temple, and that the Pharisees and authorities “were seeking to destroy him, but they did not find anything they could do, for all the people were hanging on his words.” Jesus was not immediately arrested because his boldness had attracted an army of admirers—and the Pharisees feared provoking further violence that might destabilize their power.

Interestingly, in the address in question, Francis was preaching from the temple-cleansing account in John—who is the only Gospel author that does not seem to give any explanation for why Jesus was not immediately arrested. It is disturbing to think that some well-meaning Catholics might have adopted Francis’ interpretation of this story simply because Francis could not be bothered to check the other Gospel accounts before composing his address.

In another case, the pro-passivity spin on a biblical story is so common that it is actually the prevailing view of the passage: the account in Exodus 2 of Moses’ killing the Egyptian. When this story is told, it is usually taken for granted that Moses was wrong to defend the Hebrew who was being beaten, and that the godly response would’ve been to let the Hebrew suffer and wait for God to act. Some translations of the Bible even use section headings along the lines of “Moses Commits Murder.”

This interpretation of the story has been repeated so often that I expect readers will be hesitant to consider the idea that Moses may have been in the right. Ask yourself, though: where did you really get the idea that Moses should not have defended the Hebrew? Is there any indication of this in the text, or is this simply the way the story has always been presented to you?

In fact, while Exodus 2 provides no moral commentary, an analysis of Moses’ actions appears in Stephen’s speech in Acts 7. While narrating the history of Israel, Stephen says that “[Moses] saw [a Hebrew] being mistreated by an Egyptian, so he went to his defense and avenged him by killing the Egyptian. Moses thought that his own people would realize that God was using him to rescue them, but they did not.” Stephen then recounts how the Hebrews rejected Moses’ help, saying “Who made you ruler and judge over us?”

The context of Stephen’s speech is key to understanding his point. Throughout his speech, Stephen is arguing that the Sanhedrin has rejected the salvation offered by Christ just as their ancestors rejected the salvation offered by Moses. “You are just like your ancestors,” Stephen says: “You always resist the Holy Spirit! Was there ever a prophet your ancestors did not persecute?”. Stephen’s implication is that the Israelites should have recognized that “God was using [Moses] to rescue them”—not that Moses was in the wrong.

Christian passivity therefore entraps us in circular reasoning, fails to take account of the morbid picture that the Bible paints of passivity, and warps our perception of biblical events. It looks suspiciously as if this standard is not coming from biblical interpretation at all, but from its defenders themselves—and what happens to be convenient and comfortable for them to do and say in the current cultural moment. The assumption that passivity is morally safe, let alone praiseworthy, places one’s private judgment above the authority of God. Douglas Wilson has put the problem well:

Pietists excel at… trying to be wiser than God, holier than God, nicer than God. They have made an idol out of their own emotional predilections, and like the idolater whom Isaiah made fun of, they have a hard time telling which end of the log should cook dinner and which end of it should undergo an apotheosis. Which emotion should make me have a good cry and which one should be fashioned into the standard of all righteousness?

What can be done within the church to solve this problem? First, an important objective can be achieved by ordinary educated believers in their everyday lives: challenging the clichés of Christian passivity wherever they emerge. When someone qualifies a story about Christ’s zeal with a reminder that our own zeal is sinful, politely but firmly remind them that our passivity is also sinful. Just as ordinary believers can propagate and sustain theological clichés, ordinary believers can dismantle them.

Doing so does not require that you be well-read in theology: the essence of clichés, after all, is that they are shallow. Similar theological errors, such as antinomianism, also consist largely of superficial slogans—such as responding to any statement about ethics with “judge not”—most of which can be easily exposed by any believer with a Sunday School education. Christian passivity is also like antinomianism in another sense: it should not be treated as an area on which Christians can reasonably disagree. If someone in a Bible study espouses Calvinism, a Molinist might not necessarily feel the need to respond. But the Molinist is guaranteed to respond if someone in his Bible study tries to advance antinomianism. Christian passivity should be treated the same way: the clichés that constitute it have spread far enough. Wherever you encounter them, tell them “Thus far, and no further.”

Another important change can be effected by pastors. First, though, a disclaimer: although the modern church is in dire need of broad reform and restoration, our response should not ordinarily be “pastors must do it”; pastors are busy enough and are generally doing the best they can. In this case, however, this question is largely one of pastoral ethics. If you are a pastor, and have been persuaded by even half of what I’ve written, then consider giving a sermon, or a sermon series, about the necessity of Christian boldness or zeal—perhaps based on one of the biblical examples referenced above. Jonathan Edwards’ powerful sermon “Zeal, an Essential Virtue of a Christian” might inspire you.

You might think that you’ve already done something like this. But, this time, I ask you to do something different: do not pile on so many qualifiers and disclaimers that you risk doing more to discourage boldness than to encourage it. Do not let your church go away thinking that boldness is so fraught with sin that it is best left to you, and that they’d better go on scarcely even telling their acquaintances that they are Christians. In fact, now may be the time to qualify sermons about humility and kindness with reminders to be zealous. Christian musicians and other artists can also make an impact here, writing songs and creating other content that focuses on examples of zeal from the Bible or from church history.

This brings me to a more challenging and perhaps more long-term recommendation: pastors, and other Christian influencers, should season their work with references to church history. Whether or not these references are focused on boldness per se does not even particularly matter: any significant awareness of church history will probably be effective.

One consequence of Christian passivity is that contemporary Christians cannot be at home in almost in any period of church history. If a present-day Christian attempts to read the work of almost any Christian leader from before the 19th century, he is likely to be shocked by the leader’s supposed rudeness and “unchristlikeness.” For example, in an article on Athanasius—one of the most formative leaders in Christian history—a Gospel Coalition writer observed that modern Christian readers are likely to “sniff at his angry style of writing.” In a preface to a translation of Luther—by two Lutheran academics—the translators remarked that “Luther was a person of his time, and his language expresses the roughness of the age.” Of course, it is only people in the past whose choices are explained away by their social context. Nobody reads a Christianity Today editorial and says that, after all, the author “is a person of his time, and his language expresses the gentility of the age.” Instead, it is 21st-century, middle class evangelicals who are implicitly assumed to have finally gotten christlikeness right after all these years.

To call Athanasius unchristlike is ironic, for—as we’ve already seen—Christian passivity does not actually encourage Christlikeness. The pietists admit this when they say that Christ is not to be imitated: the “Christlikeness” of Christian passivity is therefore a kind of Platonic form made up by the proponents of Christian passivity themselves. This will not suffice.

The church needs a Christlikeness which is modeled on Christ himself, and on every aspect of His character. When the church once again looks like Jesus, then—if history is any indication—more seekers than ever will say, as I once did, that “there must be something in this idea that gives it power.”

Originally published on Staseos in December, 2019. For more, follow @IanHuyett.