Understanding Teilhard, Part I: The Holiness of Evolution

A primer on the polarizing, futurist theology of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

In virtue, therefore, of his faith, the Christian is justified in claiming a place among those who work for the greatest advancement of the earth; and the soul he brings to that work will be ablaze with the fire that inspires the conqueror.

-Teilhard de Chardin, Cosmic Life

The theology of Teilhard de Chardin is famously compelling and notoriously confusing. For years, I was impressed by the ideas I had seen attributed to Teilhard in the writings of others. Like many thinking Christians, however, I had only glimpsed the controversial thinker through a glass darkly. When I attempted to crack into Teilhard’s writing directly, his often-opaque style left me discouraged.

Finally learning to understand Teilhard’s work was a breakthrough in my own theological development. Yet I've also found that my disagreements with Teilhard run deeper than I would have anticipated. In this series of short essays, I'll discuss Teilhard's personal background and views on evolution, explain Teilhard's emphasis on research as a Christian duty, address the most common accusations of heresy and error that are leveled against Teilhard, and finally analyze his views on space and the universe.

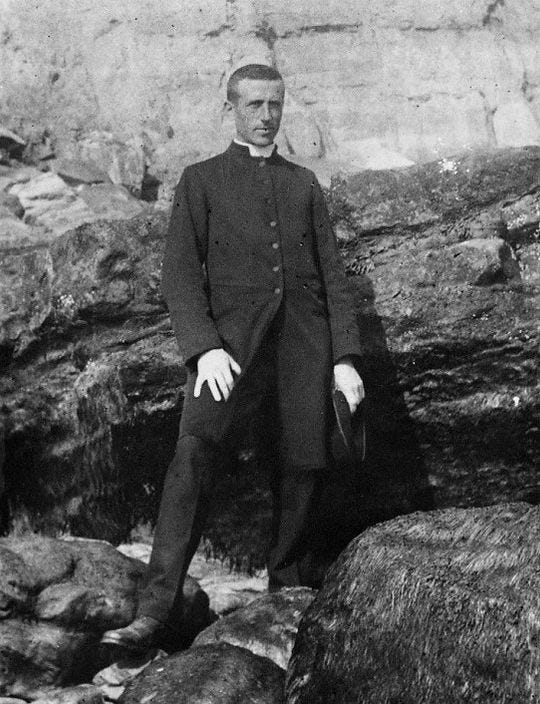

Encountering Teilhard de Chardin

I’ve wanted to understand Teilhard since I first read some references to him in Dan Simmons’ Hyperion Cantos novels. Simmons’ series is a vast science fiction epic set in a distant future in which Teilhard has been canonized as a saint and become a dominant figure in Christian theology. The novels draw on Teilhard’s ideas to explore the interplay between technology and religion.

At the time I read Hyperion, I was an undergraduate and was just beginning to develop as a Christian. My grasp of Teilhard’s eschatology consisted solely of a vague sense that he believed humans are destined to travel throughout space, subdue the universe in the name of God, and—through this process—draw closer into ultimate union with Him.

I would later learn that this impression was significantly wrong. But, at the time, I was impressed by the idea that a theologian born in 1881 had envisioned a cosmic Christian dominion. As someone fascinated by both religion and technology, I made a mental note to one day study Teilhard in more detail.

I also felt another form of immediate kinship with Teilhard. As an undergraduate, I pursued an anthropology major with a focus on physical anthropology. Besides being a theologian, I learned, Teilhard was a paleontologist who studied pre-human hominids, participating in the discovery of Peking Man.

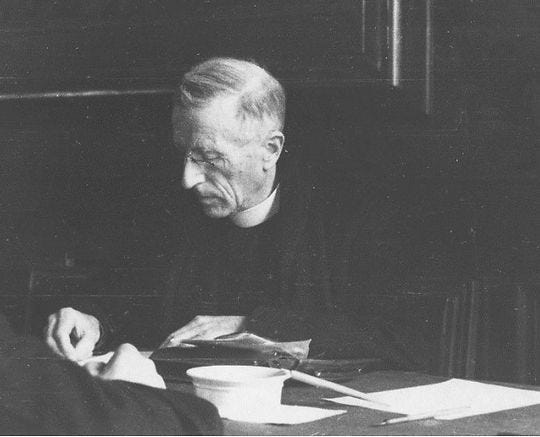

Teilhard was also a Catholic priest, and I would eventually discover that his fascination with evolution, especially with what he called “the holiness of evolution,” put him in a precarious position in the Catholic Church. Prior to Vatican II, the Church had not yet taken a formal position on evolution, and Teilhard’s fixation on it made some of his superiors uncomfortable. To this day, Teilhard’s writings remain under an official Church censure—although, paradoxically, he has been positively quoted by multiple popes, including Paul VI, Benedict XVI, and Francis. Benedict was an especially avid admirer of Teilhard, discussing his theology in multiple books.

In 1981, on the centenary of Teilhard’s birth, the Vatican released a controversial statement “on behalf of the Holy Father [John Paul II]” effusively praising Teilhard as “a man seized by Christ in the depths of his being.” The statement accurately noted that Teilhard’s theology was “restoring to men tormented by doubt the taste of hope,” while, at the same time, cautioning that his ideas raised unspecified “difficulties.”

As an undergraduate, I already had an idea that I would eventually practice law—but I still flirted with the idea of pursuing some kind of career in physical anthropology. I also enjoyed working as a teaching assistant for a biological anthropology professor and teaching two of the weekly small-group labs that accompanied her large lecture class.

Working as a teaching assistant gave me access to a huge collection of cranial casts of pre-human hominids. In the labs I taught, I set these crania around the classroom in chronological order, representing seven million years of evolution. Together, these crania demonstrated what Teilhard would have called the increasing “homonization” of life. Although I did not use these labs as a pulpit, they did give me an opportunity to subtly emphasize the congruence between religion and evolution. I pointed out to the students in my labs that seriously Christian scientists—like Carolus Linnaeus—had helped lay the groundwork for evolutionary theory, and that evolution did not presuppose “randomness” in any metaphysical sense.

But my enthusiasm did not win over a cranky Young Earth Creationist student in one of my labs. A few weeks into the course, he dropped the entire lecture and hence my lab—despite my private protestations to him that I was an orthodox Christian.

Teilhard had his own much more serious disputes with skeptics of evolution. Because the Vatican prohibited Teilhard from engaging in any public theological work, all of his most interesting and fruitful writing was done in essays circulated through private correspondence, which were only later collected into books and published.

Learning how to read Teilhard

Teilhard’s best-known book-length works today are The Divine Milieu and the The Phenomenon of Man: both of which he prepared with the intention of getting past Church censors. In law school, I tried to read The Divine Milieu twice and gave up both times, finding it borderline incoherent.

More recently, however, I learned the secret to understanding Teilhard. This epiphany came from a recorded course taught by Fr. Donald Goergen—a Dominican priest and Teilhard scholar. Goergen suggests that Milieu and Phenomenon were largely attempts to skirt Church censorship and were therefore, to a certain extent, intentionally obscure.

The real secret to understanding Teilhard, Goergen intimates, can be found in the published collections of Teilhard’s semi-private essays, which are the main focus of Goergen’s course and are written in a more relaxed and free-flowing style.

That is not to say that Teilhard’s essays are easy to understand. Streams of neologisms burst forth from Teilhard like a foaming spring. But this only underscores the fact that neither Milieu nor Phenomenon is the best introduction to Teilhard’s thought.

Goergen’s course led me to Writings in a Time of War, which contains Teilhard’s seminal essay Cosmic Life, as well as to The Future of Humanity. Together, these books answered all of my fundamental questions about Teilhard. They then helped me to fruitfully read Phenomenon.

This journey of discovering Teilhard firmly dispelled for me all the usual allegations that he held heretical beliefs such as pantheism or monism—or that he substituted technology for God. At the same time, Teilhard’s discussion of concepts like “unanimization” sometimes made me think that Teilhard brought certain misconceptions about his theology on himself—especially accusations of quasi-Eastern monism—through his own unnecessary opacity.

I’ve found Teilhard’s eschatology both challenging and sanctifying. At times, I think that discovering his writing may have opened a new chapter in my own theological development. Nonetheless, his vision is incomplete in important ways.

Evolution in Teilhard’s eschatology

As mentioned above, Teilhard is known for emphasizing “the holiness of evolution.” For Teilhard, evolution can be said to be “holy” in two ways: first, as a signpost to God Himself and, secondly, as a spark of the new world which God has promised in His revealed Word.

Teilhard describes evolution as a “process of increasing complication whereby Matter contrives to arrange itself in particles of ever greater volume, ever more highly organized.” If this language sounds similar to that used by contemporary secular futurists, this is not a coincidence. But it is these secular futurists who have appropriated and desacralized Teilhard’s thought, not the other way around. [1] Writing about Teilhard’s “Omega point theory,” which we will discuss later, the philosopher of religion Eric Steinhart has written that many secular futurists “work within the conceptual architecture of Teilhard’s [Omega point theory] without being aware of its [Christian] origins.”

For Teilhard, the fact that our universe contains a self-organizing process has significance for Christian apologetics: it suggests that we live in the kind of reality which a God would have created. In his essay Turmoil or Genesis, Teilhard writes: “Thus the World falls into order, it organizes itself, around Life, which is no longer to be regarded as an anomaly but accepted as pointing the direction of its advance (evidence in itself that the axis was well chosen!).”

While interacting with Teilhard’s work in 1994, the physicist Frank Tipler criticized Teilhard’s argument that evolution illuminates an axis pointing towards life. Tipler wrote that this interpretation was discredited in 1930s and 1940s, as scientists came to fully appreciate the role of “nonpurposive mechanisms—natural selection, random genetic drift, mutation, migration [and so on]” in evolution.

But Teilhard, who lived until 1955, was almost certainly not surprised by these mechanisms. Teilhard did not literally think that inanimate particles contained some inborn tendency to spontaneously assemble themselves into complex organisms. Instead, evolution is evidence “that the axis was well chosen [by God]” because the structure of our universe itself includes mechanisms which allow and select for greater complexity. [2]

More importantly, Teilhard is struck by the fact that evolution represents the antithesis of entropy. The evolutionary process shines uniquely against the otherwise-hopeless backdrop of a cosmos darkened by the second law of thermodynamics.

As we look around us, we see that both our bodies and the universe itself tend towards decay and annihilation. Through evolution, however, God has created a process which runs contrary to entropy and prefigures its ultimate defeat. In Teilhard’s words, “something in the cosmos escapes from entropy, and does so more and more.”

Evolution is the germ of the universe’s eventual transformation and renewal in the New Heaven and the New Earth. It is a spark of the conflagration which will consume The Last Enemy that Shall Be Destroyed. “Our world contains within itself a mysterious promise of the future,” implicit in evolution, Teilhard wrote. No sooner had I begun to imagine Teilhard’s vision of evolution as a kind of “germ” than Teilhard used the image himself: “the divine cosmos germinates from the ruins of the old earth.”

It is partly in this sense that Mankind, as the pinnacle of evolution on Earth, is made in God’s image. “It is we, without any doubt, that constitute the active part of the universe,” Teilhard writes. “We are the bud in which life is concentrated and is at work, and in which the flower of every hope is enclosed.”

Originally published on Staseos in January 2021. This column is the first part in a series on Teilhard. You can read part 2 here. For more, follow @IanHuyett.

Notes:

[1] J.D. Bernal, sometimes seen as the grandfather of secular futurism, did not publish his book The World, the Flesh and the Devil until thirteen years after Teilhard wrote Cosmic Life.

[2] Tipler has since converted to Christianity, largely due to the influence of his late friend and mentor Wolfhart Pannenberg, and seems to have moved closer to Teilhard’s view.